Wild Bird indicators

The Wild Bird Indicators are part of the government’s suite of biodiversity indicators. They report on how the UK’s bird populations have fared over many decades.

What are the Wild Bird Indicators?

The Wild Bird Indicators are annual reports on the state of the UK’s birds. They are part of the government’s suite of biodiversity indicators.

They are produced annually for Defra and NatureScot by BTO, together with RSPB and JNCC, and are based largely on volunteer bird monitoring schemes coordinated by BTO. The indicators therefore link the efforts of our dedicated volunteers directly to a policy-relevant assessment of the state of nature.

- Indicators for the UK and England are produced jointly by BTO and RSPB for Defra.

- The Scottish indicators are produced by BTO for NatureScot.

The indicators are based on population trends of bird species that are native to, and breed or spend the winter in, the UK. These population trends are calculated largely using data that is collected by volunteers, as part of national bird monitoring schemes like the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey and the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey.

The indicators group breeding birds by habitat: farmland, woodland, uplands, waterways and wetlands, and marine and coastal areas, and most are based on datasets that stretch as far back as 1970. This means that indicators are a useful tool for examining how birds associated with different landscapes have fared over many decades. The indicators also report on the state of our internationally important wintering (i.e. non-breeding) wetland and coastal birds.

How are the indicators developed?

To provide an overview of how birds are faring in each habitat, researchers from BTO and RSPB combine the population trends of breeding birds associated with each habitat to create ‘multi-species indicators’ – an aggregate which ‘indicates’, on average, how birds in that habitat are faring. Each indicator is then assessed over the long term and the short term to examine how bird populations have changed over time.

Researchers can also divide the data for each indicator more finely to provide more detailed insight into different groups of birds. For example, the wetlands and waterways indicator combines the population trends of all the native breeding bird species associated with those habitats in the UK, but it can also be broken down to examine the population trends of birds associated with slow-flowing and standing water, reedbeds, fast-flowing water or wet grasslands.

Learn more about how the indicators are developed on the Defra website:

- An introduction to the Wild Bird Indicators

- Wild bird populations in the UK: Frequently asked questions

Understanding the indicator graphs

When looking at the graphs for each indicator, it is useful to bear the following in mind:

- Numbers in brackets refer to the number of species in each group (when associated with a specific line on the graph) or in the indicator as a whole (when associated with the graph title).

- The individual points on the graph show the specific value of the indicator for each year.

- The lines on the graph are known as the 'smoothed trend' and show the ‘line of best fit’ for the individual points. They allow us to see the overall trend in the indicator more clearly.

- Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval. This is a statistical measure which represents a range of values around the smoothed trend; there is a 95% probability that the smoothed trend falls within this range. The narrower the confidence interval around the smoothed trend, the more confidence we can have that the statistical methods have produced an accurate trend.

- The index shown on the graph does not represent the actual number of birds, but is a percentage of an initial baseline population (see below).

What is an ‘index’?

By analysing the annual monitoring scheme data collected from the same sites, researchers can compare how bird populations are changing.

- The total estimated bird population at the beginning of the data period is known as a ‘baseline’.

- Changes to the population are measured using an ‘index’ – a percentage of the total estimated bird population at the beginning of the data period.

When you look at the indicator graphs, the values of the individual points and smoothed trend lines show you the population for each year as a percentage of the population size at the beginning of the dataset.

For example, if the value is around 20, that means that the current population size is only 20% of the baseline population size – in other words, the population has declined by 80%. Conversely, if the value is 120, that means the current population is 120% of the baseline population size – it has increased by 20%.

You will sometimes see the baseline population index value set to 1 instead of 100. In this instance, 1 is equivalent to 100%, 0.8 to 80% and so on.

Latest updates

The latest updates of the UK and England bird indicators based on the population trends of wild bird species were published on 7 November 2023. They report on the population trends of birds over the long term (in most cases, since 1970) and the most recent short-term period (in this case 2017–22).

Read a summary of the latest updates to each indicator:

You can also view the full details on the Defra website:

- Indicators for the UK as a whole

- Indicators for England alone

Wild Bird Indicators for the UK

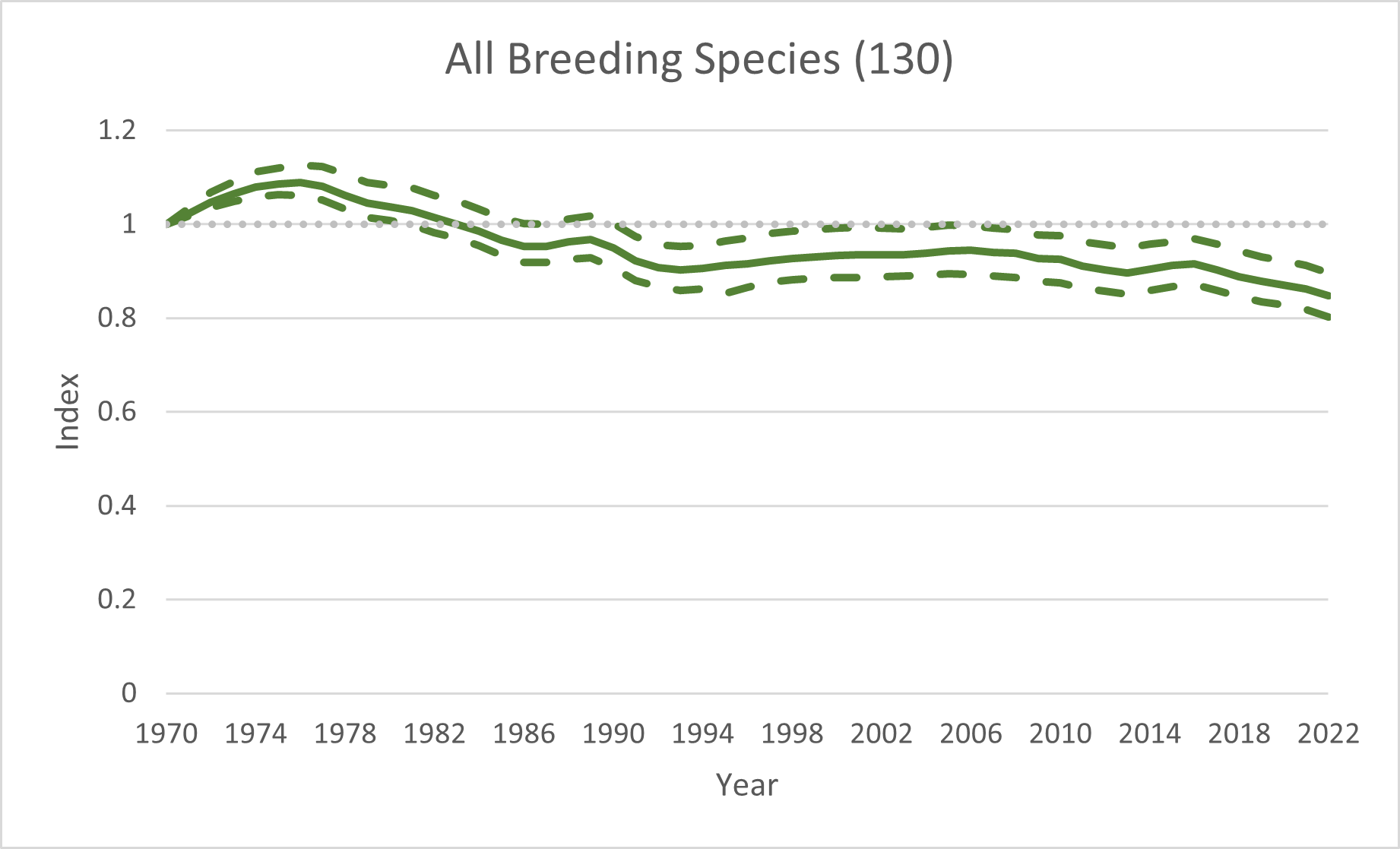

Indicator for all UK breeding bird species

The combined ‘all-species indicator’ is comprised of the population trends of 130 bird species that breed in the UK. It has shown a shallow decline of 15% over the last 45 years, and has declined 6% over the most recent five-year period (2017–22).

This overall pattern masks considerable variability between the trends for different species, with some increasing and some decreasing. Changes by habitat are summarised in each of habitat-specific indicators.

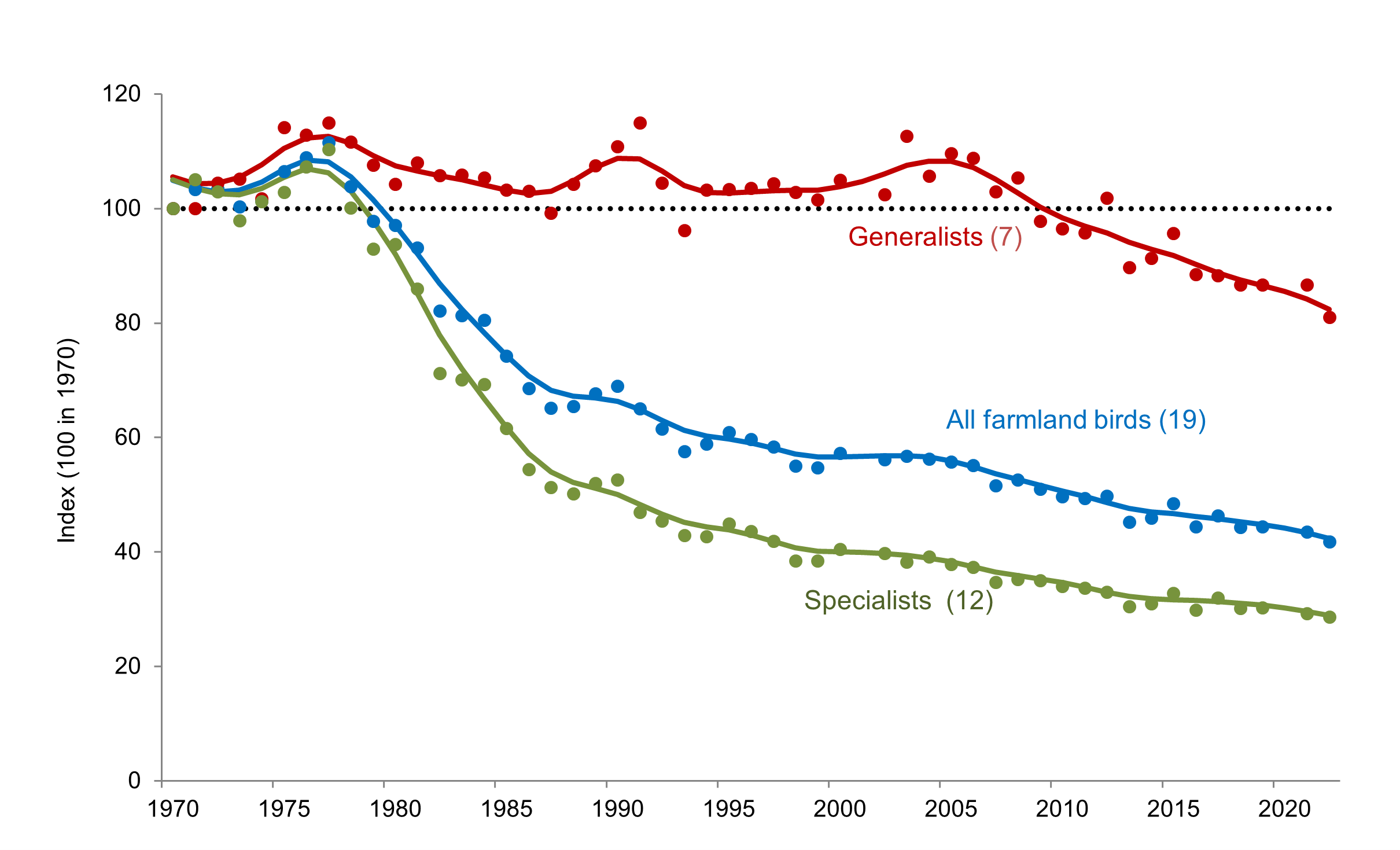

UK breeding bird farmland indicator

As seen in previous years, the breeding farmland bird indicator continued to fall and has declined by 60% between 1970–2022.

Whilst most of these declines occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s, declines are ongoing and there was a marked short-term decline of 8% between 2017–2022.

Farmland specialists showed the most prominent declines; for example, Corn Bunting, Grey Partridge, Turtle Dove and Tree Sparrow have all declined by at least 90% since 1970. This is largely attributed to changes in the way farmland has been managed over the past five decades, such as spring sowing and the loss of winter stubble, loss of hedgerows and other semi-natural features, and increased fertiliser and pesticide use.

However, the numbers of some farmland specialists (e.g. Stock Dove and Goldfinch) have more than doubled since the 1970s. This illustrates that responses to pressures vary between species, with some species better able to cope by exploiting new crops and food sources, or benefitting from agri-environment schemes.

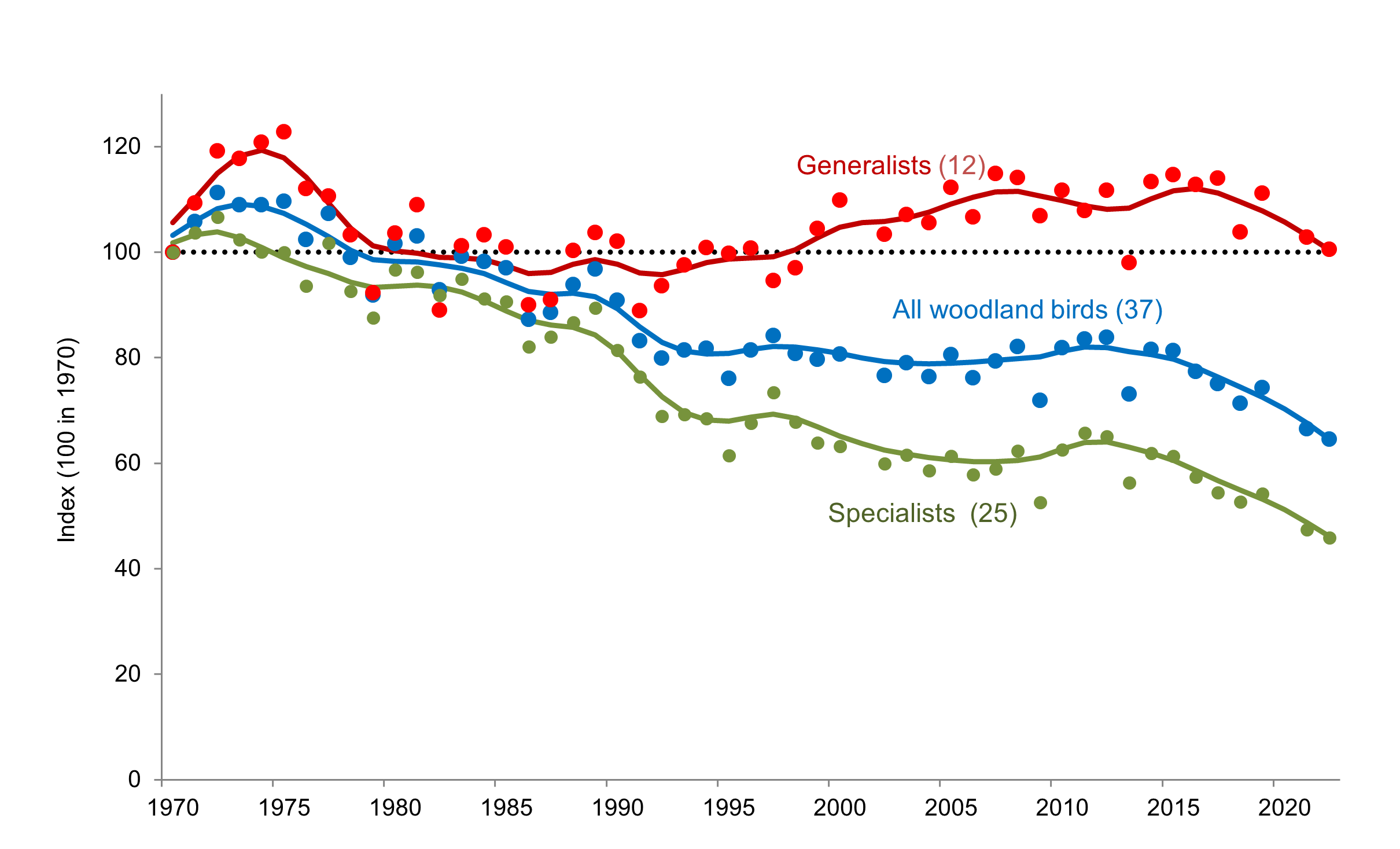

UK breeding woodland bird indicator

The breeding woodland bird index for the UK has declined by 37% between 1970–2022, and by 15% just over the recent short-term period from 2017–2022. This means that woodland birds are currently our most rapidly-declining group.

There are significant declines in many woodland specialists, but also in long-distance migrant species that breed in our woodland in the summer and spend winters in sub-Saharan Africa.

Generalist woodland species, typically those that also breed in gardens or wooded areas of farmland, show little overall change – about a 5% decline since 1970. However, some earlier increases have been followed by a sharper decline of 10% in the last five years.

Woodland species such as Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Spotted Flycatcher and Willow Tit have shown the steepest declines (greater than 80%) since 1970.

Conversely, numbers of Blackcap and Nuthatch have almost doubled, and the Great Spotted Woodpecker is more than three times as abundant as it was several decades ago.

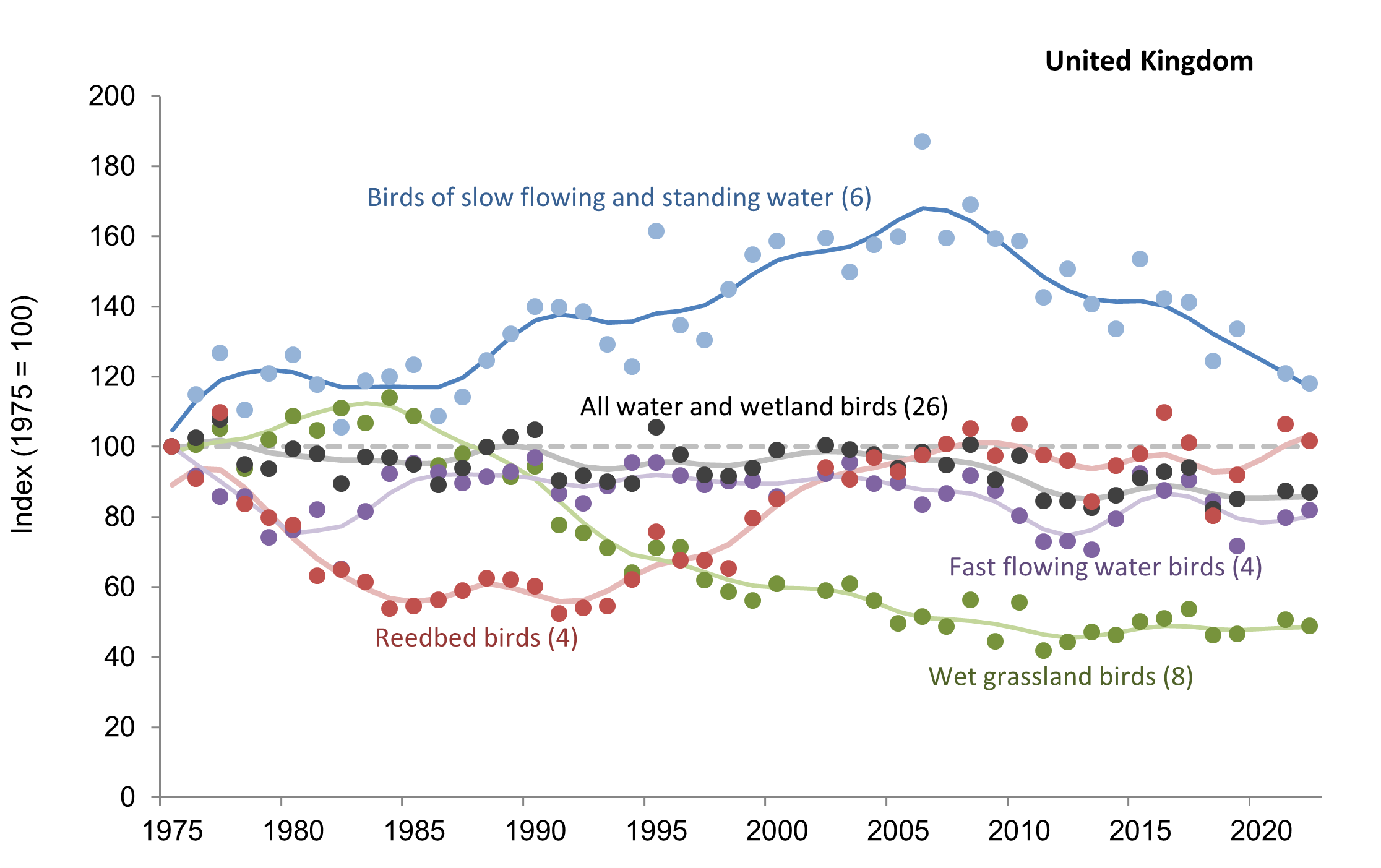

UK breeding birds of wetlands and waterways indicator

The breeding water and wetland bird index for the UK fell by 13% between 1975–2022, but over the short term shows little change – a decline of only 3%.

Over the long term, species associated with slow-flowing and standing water, and with reedbeds, fared better than those associated with fast-flowing water or with wet grasslands.

Lapwing, Redshank, Snipe and Common Sandpiper showed the strongest declines over the long term, whereas Mute Swan and ducks including Mallard, Tufted Duck and Teal have increased.

This indicator is based on trends calculated from a combination of Breeding Bird Survey and the more riparian-focused Waterways Breeding Bird Survey data, as well as their predecessors.

UK upland breeding bird indicator

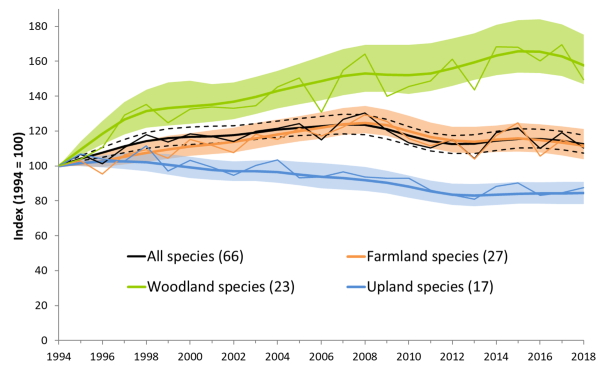

This update of the wild bird indicators includes for the second time an Upland Bird Indicator, which has been developed over the past few years.

This is a composite indicator constructed from the population trends of upland bird specialists as well as the populations of more widespread species monitored on upland Breeding Bird Survey sites. It is largely based on data from the Breeding Bird Survey, which began in 1994, so the indicator covers the period from 1994–2022.

Overall, the upland bird indicator declined by 13% between 1994–2022, and by 5% between 2017–22.

However, breaking down the 32 species into three subgroups – upland specialists, upland riverine species, and non-specialists with large populations in the uplands - reveals further patterns: upland specialists have declined by 20% since 1994, upland riverine species by 12%, and upland populations of other species by only 4%.

Breeding seabird indicator

The breeding seabird indicator has not been updated this year. This is due to a combination of issues related to restrictions on site visits due to COVID-19 and more recently to avian influenza, as well as the transfer of the coordination of the Seabird Monitoring Programme from JNCC to BTO.

The last reported seabird indicator is republished in the Official Statistics and it is hoped that the seabird indicator will be updated in spring 2024.

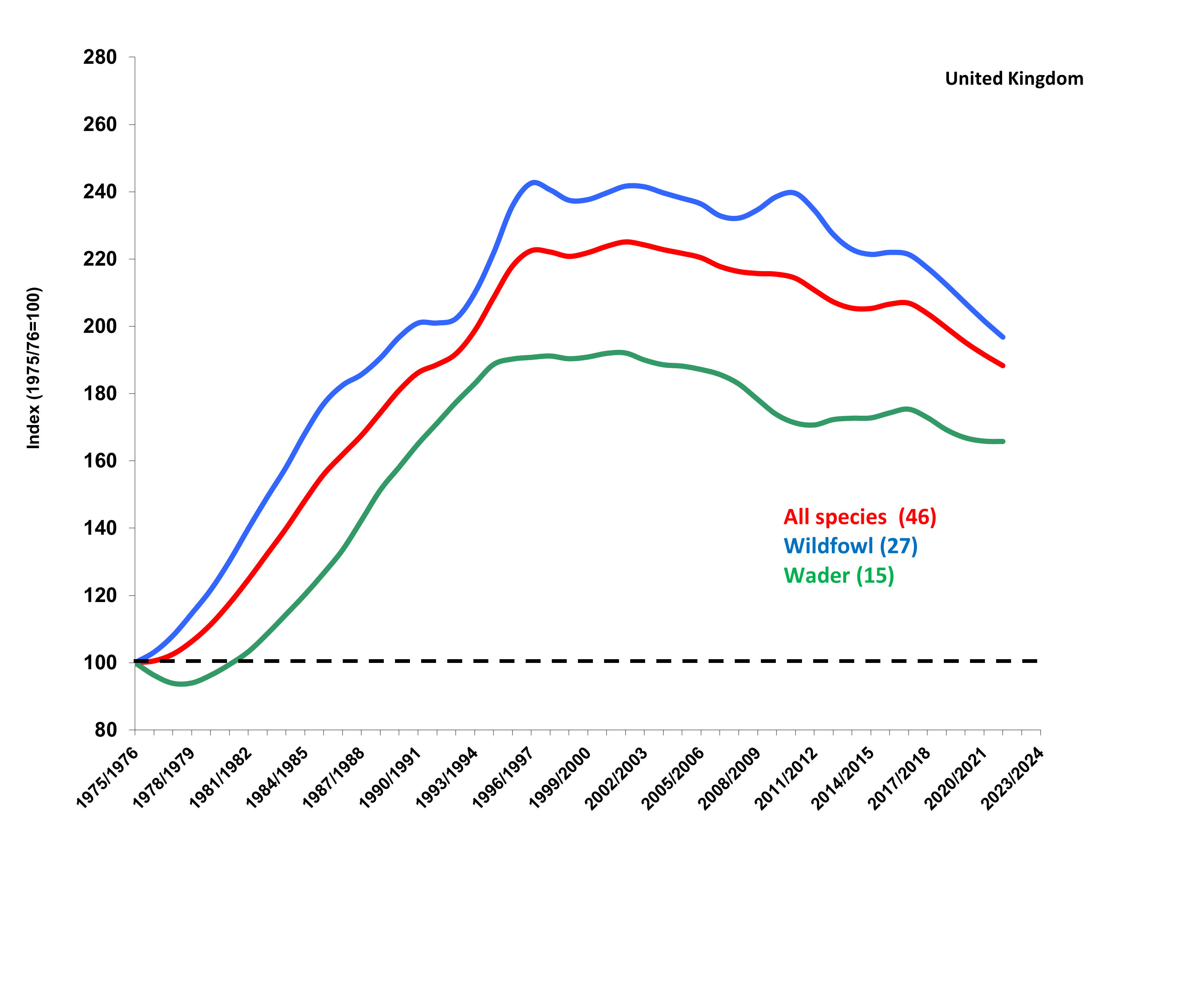

Wintering waterbird indicator

This indicator monitors the internationally important numbers of waders, ducks, geese, swans and other waterbirds that winter on our coasts and wetlands since the mid 1970s. It is largely based on data collected by the Wetland Bird Survey.

COVID-19 restrictions prevented a full set of Wetland Bird Survey counts in the 2020/21 winter, so the indicator was not updated in 2022. However, the indicator has been updated in this publication using the most recently available data, from the 2021/22 winter.

Wintering waterbirds in the UK are comprised of birds from breeding populations that fall both within and outside the UK. For example, the wintering Curlew population is made up of birds that breed in the UK's uplands and wet grasslands as well as birds that breed in Continental Europe. For this reason, the wintering waterbird indicator represents the trends of several different breeding populations of the same species.

In the winter of 2021/22, the wintering waterbird index was 88% higher than in the winter of 1975/76. However, numbers have been in decline since the peaks of the mid 1980s and the indicator fell further, by 9%, between the winter of 2016/17 and 2021/22.

Examining the indicators for species groups, wildfowl have shown more overall increase than waders, but the indicators for both are broadly parallel. The indicators for both groups also include species with very different trends – for example, numbers of Avocet and British/Irish wintering Greylag Goose increasing in contrast to steep declines in Dunlin and Bewick’s Swan.

There is good evidence to suggest climate change has had a significant impact on the indicator in recent years. Milder winters across Europe mean the wintering ranges of many species, including Mallard, Pintail, Goldeneye, Pochard, Bewick’s Swan, Ringed Plover, Curlew and Bar-tailed Godwit are increasingly shifting away from the UK.

In addition, local changes such as wetland creation and shifts in agricultural management have also had a mixed impact on waterbird populations within the UK.

Indicators for Scotland

The latest figures were released in November 2019.

Terrestrial breeding birds

The indicator shows a positive long-term trend for woodland birds in Scotland, with this group increasing by 58% between 1994 and 2018.

Chiffchaff, Great Spotted Woodpecker, Blackcap, Great Tit, Bullfinch, Lesser Redpoll and Tree Pipit have all increased in abundance, some of which can be attributed to northward shifts in breeding range and changes in the extent of suitable habitat.

The indicator for farmland birds is also positive, with Goldfinch, Whitethroat and Reed Bunting among the species contributing to a 12% increase since 1994, albeit following declines in range among many farmland species since the 1970s revealed by the BTO's bird atlases.

Upland birds declined by 15% during the BBS period, populations of Dotterel, Curlew, Black Grouse, Common Sandpiper and Hooded Crow having decreased by more than 50%. Most of these species have been negatively affected by changes in land management or climate change which is also potentially linked to a northward shift in the centre of the Carrion Crow/Hooded Crow hybrid zone and consequent decline in Hooded Crows.

Many species exhibited a short-term decline between 2017 and 2018, probably as a result of the so-called 'Beast from the East'. These declines were most common among woodland residents, with Wren, Bullfinch, and Goldcrest the most strongly affected. Robin, Treecreeper, Great Spotted Woodpecker and Lesser Redpoll also declined, though to a lesser extent.

Wintering waterbirds in Scotland

The latest Biodiversity Indicator for Wintering Waterbirds in Scotland was released by NatureScot in September 2021. This indicator tracks the population trends of 41 species, which are primarily counted by volunteers taking part in the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS), supplemented with additional targeted counts for geese and swans, and periodic surveys of rocky shore waders (the Non-Estuarine Waterbird Survey, NEWS).

This indicator showed that overall waterbird numbers have decreased by 7%. Much of this decline is explained by waders, with numbers for the 14 species monitored 58% lower than in winter 1975/76. There was more positive news for ducks and swans (16 species), which increased by 21%, and geese (seven species/populations), which rose in number by 274%.

Our programme of research in Scotland aims to better-understand the issues affecting our bird populations in order to inform future management. Current work programmes include collaborative research on breeding wader management and conservation, detailed studies of Short-eared Owl ecology and movements, and work to understand how woodland expansion and regeneration can impact bird populations.

Share this page