Migration blog review of 2021

Scott’s role includes the day-to-day running of BirdTrack: updating the application, assisting county recorders by checking records and corresponding with observers.

Relates to projects

Spring

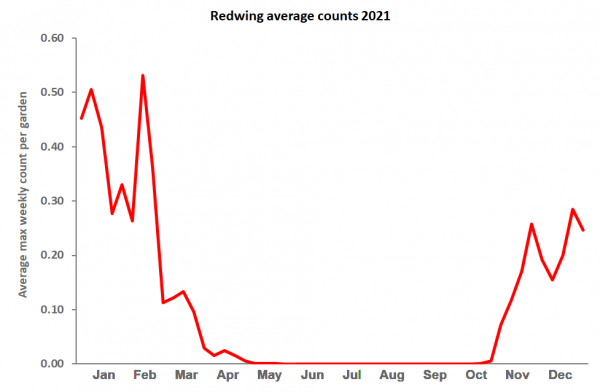

Spring migration typically starts in March but movements can happen at any time of the year in response to cold weather and storms. The first few weeks of the 2021 saw snow, ice, flooding and stormy weather across large parts of the country and, as a result, Redwings and Fieldfares moved into gardens in search of berries and fallen apples. Little did anyone know that these cold conditions would be an on/off feature right through to early May!

A Wheatear photographed on the 8th of February on the Isle of Wight was a real surprise and hinted at the possibility of an early spring. Indeed warm southerlies at the end of the month brought Saharan dust and more early summer migrants – Sand Martin, Swallow, House Martin, Little Ringed Plover, Osprey, Whimbrel and Stone-curlew were all reported earlier than is usual.

As the spring progressed, the dominant feature was cold northerly winds that at times brought spring migration pretty much to a halt. However, as with all weather systems, there were windows in the weather that allowed birds to move, with one such warm spell in early April seeing a big arrival of Swallows and House Martins. These two species seemed to really struggle to push north in the colder than average conditions. Another brief period of warmer weather occurred in mid-April and the change was instant with the first Lesser Whitethroats, Wood Warblers, Redstarts and Whinchats arriving en-masse, along with a couple of classic spring overshoots in the shape of Hoopoe, Purple Heron and a Red-rumped Swallow. By the month-end, most summer migrants were back, though in some cases in lower numbers and with a later average arrival date. This wasn’t the case for all species and one that passed through Britain and Ireland slightly earlier and in good numbers was Bar-tailed Godwit. A spike in reports at the end of April included an amazing count of 1,806 at Severn Beach, Gloucestershire on the 26th of April, many of which will have been in their brick-red breeding plumage.

The weather might have made early May feel more like early April, but although migration was slowed a little, later arrivals came in pretty much on cue. Swifts were here on time but again seemingly in lower numbers than would be expected, while Garden Warblers began to be heard in thickets and hedgerows. Wader movement is a feature of early May and last year was no exception, with a large movement of Whimbrels and Common Sandpiper being seen. Waders typically pass through later than passerines as they breed much further north and need their breeding areas to be free of ice and snow before they arrive.

Spring 2021 also brought with it a handful of rarities including a Common Rock Thrush (St Marys, Isles of Scilly) and a Calandra Lark, (Fair Isle, Shetland). The Northern Mockingbird that was found in early February in Exmouth, Devon, went for a fly around turning up at Pulborough, Sussex then Newbiggin-by-the-Sea, Northumberland.

One of the stand out stories from last spring were the apparently low numbers of House Martins across many parts of Britain and Ireland. The early part of their spring migration started off well with House Martins arriving when expected as they pushed northwards on the warm weather of early April. However, the following weeks were dominated by colder weather and northerly or westerly winds and, as a result, reports slowed and in late April actually decreased compared to the previous week. Although reports did recover in the next couple of weeks, the general reporting rate of House Martins remained below expected levels. The maps from the EuroBirdPortal, which use BirdTrack data, show this striking reduction in reports compared to 2020.

So, Spring migration in 2021 wasn’t typical for many summer visitors. Most were late arriving and, like House Martin, appeared in lower numbers than would be expected. We know the unseasonably cold weather across most of southern Europe held birds up but what did these birds do? Did many of them perish, or not bother moving north once the weather window opened? We might have a better idea once the 2021 numbers have been crunched.

Autumn

For many birders, autumn is synonymous with migration and the prospect of seeing a variety of rare and scarce species alongside more familiar passage migrants. Whilst we may think of September and October as the key months for autumn migration for many bird species the ‘autumn’ return migration can begin in July. Spotted Redshank is one of the first to return and last year was no exception with returning adult birds, most likely females that have left the males to raise the young, noted from early July with reports continuing to build during the month. This delicate wader with its jet back plumage and fine red-tinged bill and red legs is a delight to see and hinted at what was to come as Ruff, Green Sandpiper, and Common Sandpiper numbers also increased throughout July.

August, for many parts of Britain and Ireland, was dominated by heavy showers brought in on Atlantic depressions, and it was the associated south to south-westerly winds that heralded the start of the seawatching season. Both Cory’s and Great Shearwaters were seen from several Cornish headlands, as well as from dedicated pelagic trips from the Isles of Scilly and it was these pelagic trips that, as expected, produced the biggest numbers of Wilson’s Petrels. This tiny ocean wanderer has become a feature of late summer and 2021 was no exception. Up to 10 birds were seen from several trips off the southwest of the Isles of Scilly, while a single bird seen from a boat off the Shetland Isles. Towards the end of August, a prolonged period of north-easterlies was welcomed with a flood of common migrants, including Pied Flycatcher, Redstart, Whinchat, Whitethroat, and Willow Warblers at many a coastal watchpoint. A scattering of scarcer species was also seen, with Barred, Icterine, and Greenish Warblers reported from a number of locations.

As 2021 progressed into September, the inevitable interrogation of weather charts and forecasts began. With many of us swapping a trip abroad for a week or two at a prime birding spot in Britain and Ireland, more pairs of eyes scrutinising these hotspots made expectations perhaps higher than normal. The month started with another period of northerlies bringing with it a glut of Sooty Shearwater sightings, mainly along North Sea coasts with some locations recording high double-figure counts, such as 80 past Flamborough Head on the 1st September. A supporting cast of Balearic Shearwaters, Great, Arctic, and especially Long-tailed Skuas was most welcome and provided a distraction from what had been a slow start to autumn passerine migration. A brief period of easterlies during mid-September hinted at what could have been with an increase in passage migrants from Scandinavia stopping off on their southward migration. Pied Flycatcher, Wheatear, Whinchat, and Wryneck were to be found at a number of locations, whilst a Green Warbler found at Buckton, East Yorkshire, delighted those seeking something a little rarer. However, it was starting to become clear that this wasn’t a classic year. As many birders headed to the islands at the southern and northern ends of Britain – Scilly and Shetland – dreams of a bounty of vagrants from Asia or the Nearctic were proving to be just that.

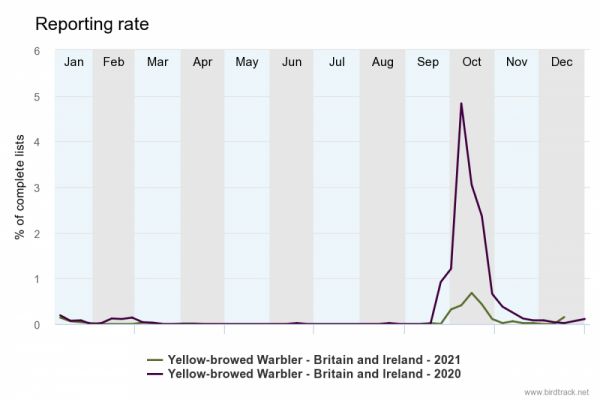

Yellow-browed Warbler is the quintessential star of the autumn, with this Siberian sprite sure to brighten even the dullest of days. However, 2021 proved to be one of the poorest years for the species in in recent times, with birds arriving much later than normal and in much lower numbers. The first notable arrival of Yellow-browed Warblers didn’t happen until the end of September, some two weeks later than expected with the majority of these birds seen across the Shetland Isles. This feature of birds arriving later and in lower numbers was repeated for a number of species: Brambling, Redwing, and Ring Ouzel all showed a similar pattern, most likely a result of unfavourable conditions. These included almost constant westerly winds that kept birds on the near-continent, and warmer weather that prevetned them from being forcing to move south. This westerly airflow did, however, deliver a number of Nearctic vagrants, especially after the remnants of hurricane Sam hit Britain and Ireland in early October, with a Rose-breasted Grosbeak (Cape Clear, Ireland), Blackpoll Warbler (Galley Head, Co. Cork), Upland Sandpiper (Dursey Island), and up to 7 Red-eyed Vireos scattered across the country.

Towards the end of October the flavour of migrants turned more wintery, with Whooper Swans, Pink-footed Geese, Pintail, Wigeon, Teal, Shoveler, and Redwings all arriving in good numbers. Joining the Redwings were plenty of Blackbirds, sometimes sharing the same feeding areas before pushing inland and, in the case of the occasional Ring Ouzel, migrating much further south. The bird of the year for many was found on the island of Papa Westray, Orkney at the end of October. The 2nd Varied Thrush for Britain, following one in Cornwall in 1982 was for many the saviour of what was a poor autumn for rare birds and may even be the bird of their life given that many thought this species would never occur in Britain again.

By November migration slows and, generally, at this time it is often only colder weather that drives birds to migrate. The warm weather in Novemeber 2021 is the likely cause of Fieldfare being obvious by their absence. Fieldfares typically arrive across Britain in mid-October but in 2021 very few birds were reported during October and it wasn’t until mid-November that the first significant arrival occurred, with large flocks reported across a broad front; a huge count of 18,080 passed over Wintersett Reservoir, West Yorkshire on the 4th of November. Using the fantastic EuroBirdPortal maps it is possible to compare side by side, this year and last year, the movements of Fieldfare across Europe. These maps show us that the majority of Fieldfares remained in Finland and didn’t begin to move out until early November. Warmer temperatures and the lack of snowfall meant birds were still able to find food so had no need to migrate as early as in previous year. Could this be a pattern we continue to see in the future?

Share this page