BirdTrack migration blog (mid-July - mid-August)

As we progress through the summer towards early autumn we are still a few weeks away from any large-scale migration. However, the next month will give us a hint of what is to come later in the year.

Scott’s role includes the day-to-day running of BirdTrack: updating the application, assisting county recorders by checking records and corresponding with observers.

Relates to projects

Mid-summer is typically quiet in the way of migration, and this year has been no different. As mentioned in the last blog, the first returning waders have arrived with Spotted Redshank, Green and Wood Sandpiper and Curlew turning up across Britain and Ireland. In the case of Spotted Redshank and Green Sandpiper, these birds will be failed breeders or female birds that have left the duty of raising their offspring to the males. Common Sandpiper, on the other hand, is an early breeder, so most of the birds arriving now will be a mix of adult birds and this year's young, with the majority of breeding areas vacated by the end of July.

The last few weeks have also seen a few scarce species scattered across Britain and Ireland, with the highlights being Turkestan Shrike (East Yorkshire), Elegant Tern (Co Wexford), Eastern Black-eared Wheatear (Co Clare), and a handful of Caspian Terns.

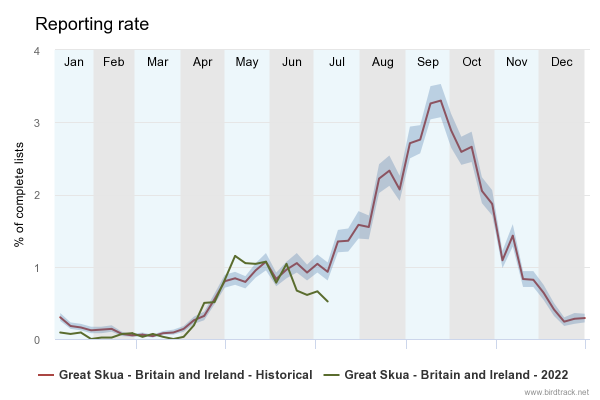

The biggest story of the summer, though, has been the devastating effects of Avian Flu, and we wait with some trepidation to see how this outbreak impacts the reports of skuas, terns, and other seabirds when they start to migrate later in the year.

BirdTrack's reporting rate for Great Skua is already showing a worrying dip and could be a result of the dramatic impact avian influenza has had on the breeding populations. However, more research is needed to establish whether avian influenza is the cause of the drop in reports.

Species focus - Aquatic Warbler

As a rare visitor to Britain and Ireland, Aquatic Warbler might seem like a strange species to focus on - but it hasn’t always been as rare a visitor as it is now.

During the 1980s and 1990s Aquatic Warbler was an expected autumn migrant in small numbers, with most being seen in the south and southwest. During this period, almost 700 individuals were ringed in this region!

Adult Aquatic Warblers begin to leave their breeding grounds in late June, with young birds doing the same about a month later. As a consequence August was, and still is, the best month to encounter one on these exciting birds on our shores.

The change from scarce migrant to rare visitor is a result of a declining population, which has led to a subsequent contraction in the breeding range and altered the number of birds passing through Britain on migration. Aquatic Warblers no longer breed in the western part of their former range, with populations centred instead on Belarus and Hungary. This may negate the need to migrate through southern Britain on the way to West Africa, but the majority of Aquatic Warblers leaving their breeding grounds may simply head south and west from Belarus, no longer getting close to British shores. The current population estimate is quite broad, at 22,000-32,000 individuals and falling. The justification statement in the Birdlife Data Zone for Aquatic Warbler being listed as Vulnerable on the European Red List of Birds is sobering:

‘The population is believed to continue to decline at a moderately rapid rate following a major decline caused by habitat destruction during the second half of the 19th century. The species, therefore, qualifies as Vulnerable. Targeted surveys with a consistent methodology have improved the estimates of the population size and with that monitoring of trends, however, declines continue even in areas receiving extensive conservation efforts; outside the core range rapid declines continue and further national extinctions are likely.’

It would seem that occurrences in Britain may become even rarer in future, but during August it is always worth checking out reedbeds, or more precisely, the sedgey, rushy bits alongside them which Aquatic Warblers favour - but bear in mind that most birds of this species will be seen in south and southwestern England.

Looking ahead

The next few weeks into mid-August will see a steady increase in migration.

The main species on the move at this time of year are seabirds, some of which are actually here as part of a huge migration that will see them heading back to the South Atlantic, where they will breed during our winter. Great Shearwater breed in Tristan da Cunha, Gough Island, and the Falkland Islands, undertaking a huge circular migration that crosses the equator and into the North Atlantic, where they can be seen from boats and headlands around Britain and Ireland from late July onwards. This large shearwater arrives slightly later than Cory’s Shearwater, which is a visitor from the islands of the Atlantic where it breeds. The number of birds that are reported each year is very weather dependent, with strong south-westerlies giving the best chance of a sighting. The headlands of Cornwall, Devon, and Pembrokeshire are prime locations to see these ocean wanderers when the weather is favourable. Late July and early August is also a good time of year to see Manx and Balearic Shearwaters, again mostly along southern coasts, but they can sometimes occur further north if strong southerlies push the up the Channel. Mixed in with these will be the occasional Storm Petrel or the first Arctic Skuas of the season.

Many of our summer visitors will have raised their first broods of young and these will start to disperse. These young will include Sedge, Reed, Grasshopper, and Wood Warbler, and they can often be found away from their favoured habitats as they search for feeding sites along their migration routes. Swift, although being one of the last of the summer migrants to arrive, is also one of the first to leave, with late July typically being the start of their return migration. Screaming parties of Swift start to form larger and larger flocks, and given the right conditions can pass through some locations in large numbers in a seemingly endless stream - a true migration spectacle.

During late summer, look out for Shelduck creches, where one pair of adult birds takes care of several broods of young whilst the parents of these young fly off to traditional moulting sites. There is still work being done to find out which of the moulting areas individual populations use; you can find out more, including how you can help, via the Shelduck Migration website.

The coming month can produce some very rare species, so it's also worth keeping an eye out for anything unusual. The more likely rarities to turn up include Wilson's Storm Petrel, Whiskered and Caspian Tern, Night Heron, Black-winged Pratincole, and Lesser Grey Shrike.

And, as always, don't forget to add your records to BirdTrack. This is even more important in the context of the outbreak of Avian Influenza, as BirdTrack records can be rapidly used in research to inform conservation action.

Learn more about BirdTrack

Share this page