Tracking Short-eared Owls: Notes from the field

Why would anyone choose to spend a winter’s night out on a cold Orkney moor? Ben Darvill gives an insight into the dedication of Short-eared Owl fieldworkers, and their amazing discoveries.

Ben is responsible for developing and supporting BTO volunteer efforts in Scotland.

Birdwatching doesn’t often send your pulse sky high, but it turns out that trying to find a Short-eared Owl nest does.

To fit a tag you need to catch an adult, and to do that you need to find the nest. So on a fine May evening in 2017 I found myself crouched amongst the heather, looking out over an expanse of moorland, hoping. I’d seen adult owls in the area and I had my suspicions, but I wasn’t sure. I forget how long I waited - an hour perhaps, maybe two. Then an owl appeared, carrying a vole… Birdwatching doesn’t often send your pulse sky high, but it turns out that trying to find a Short-eared Owl nest does.

An adult carrying food is a good sign - it suggests that there’s a nest nearby. It perched briefly on a tussock, then flew a short distance and dropped out of sight. A few seconds later it was up and off, without the vole. I stared, hard, trying to find something distinctive amongst the sea of cotton grass, rush and heather. With my eyes fixed on a nondescript tuft, I set off across 500 metres of heathland, trying not to blink. Walking across uneven ground without looking down isn’t easy, so I stumbled and lurched my way towards the tuft, desperately trying not to lose sight of it.

“Don’t make eye contact,” John had said (John Calladine, BTO Scotland’s Senior Ecologist and Short-eared Owl project lead). How do you look at an owl without making eye-contact? As I approached the tuft my pulse raised further still. Then, there they were: the piercing yellow eyes of the female on the nest, staring right at me! I tried not to look, marked the location on my GPS, and beat a hasty retreat. Little did I know how significant that owl, which we caught, tagged and released a few days later, would turn out to be.

Extraordinary movements

The technology in these tags is incredible. They weigh just 11 grams – less than a two pound coin – yet house a solar panel, battery, GPS receiver, satellite transmitter and a miniature computer. The chip is programmed to record a fix every three hours (light levels permitting), and to relay this information to John via the satellite network. The precise GPS fixes have given us fine-scale detail on habitat use – information which is already forming the basis of land management recommendations which we hope will help conservation efforts.

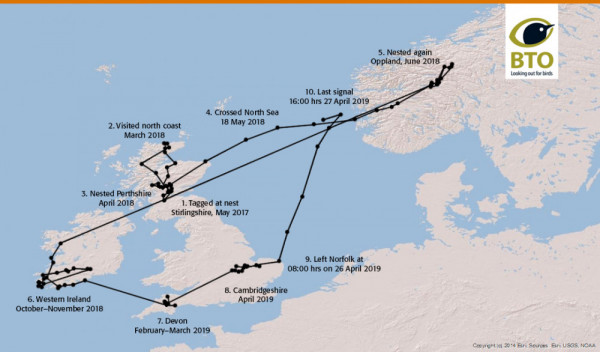

It’s the longer-distance movements which have really grabbed the headlines, however, and of the five birds tagged in 2017, ‘mine’ turned out to be the star. She overwintered locally, then wandered around Scotland in March 2018 – perhaps looking for higher vole densities, or a better mate? By late-March she had settled down to breed, back in Perthshire. Then, not long after her chicks had hatched, things took an unexpected turn. She abandoned her territory, leaving the male to rear the chicks, then flew to Norway and bred again! Two broods in two countries in the same year, with different mates – quite extraordinary.

Her unexpected wanderings didn’t stop there, however. In the months that followed we tracked her movements to Ireland, Devon and Norfolk, and recorded her final hours as she attempted to migrate back to Norway in spring 2019, sadly perishing in a storm close to the Norwegian coast.

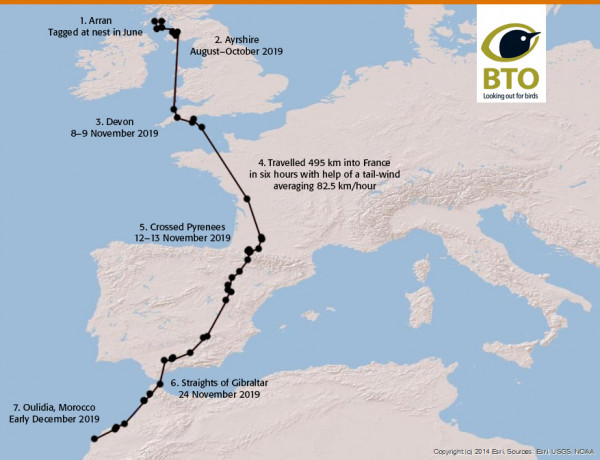

At the time of writing, 10 birds have been tagged in Scotland, each with a unique story to tell. Another female, tagged on Arran in June 2019, ranged over SW Scotland before flying south to Devon. After a couple of days here she continued on, using a strong tail wind to travel 495 km into France in just six hours (averaging 82.5 km/h!). She crossed the Pyrenees on 13 November and the Strait of Gibraltar on 24 November, settling in Morocco. Her tag is currently dormant, but is due to reactivate in early February – we can’t wait to find out where she is now!

Short-eared owls don’t seem to live very long (the longevity record for a ringed bird is around 6.5 years) so it’s no surprise that some of our birds haven’t survived. Information about where and when they die can be useful, of course. A different Arran female provides one such example. She remained on the island until October, then headed south, transmitting from Ireland, Wales and the south of England on her way to Brittany. Sadly her movements then stopped abruptly on the verge of the A28 motorway, strongly suggesting that she was killed by a vehicle. We’re used to seeing Kestrels hovering over motorway verges (though less commonly in recent years) and I wonder whether she was hunting when she died.

A new milestone

Thanks to extraordinary dedication and perseverance, John and co-worker Neil Morrison recently achieved a significant project milestone. In December of last year, when most of us were enjoying mulled wine and mince pies, John, Neil and local collaborators were out on a cold Orkney moor in the middle of the night. Fine-mesh ‘mist nets’ were erected and an array of loudspeakers played owl calls and vole squeaks. Their efforts were rewarded with the sum total of nothing at all – not one single owl. But in January 2020 they tried again, this time on Arran. There were four different teams out this time, and they were in luck, catching a single male Short-eared Owl. This was the first time that they’d managed to catch and tag an owl outside the breeding season.

What next?

The job isn’t over yet. John aims to tag up to 25 Short-eared Owls from sites across their breeding range in the UK. By following individuals from a range of locations he hopes to better understand how variation in local conditions affects their breeding success. It’s possible that local habitat composition, food availability or predator density could be affecting the owls’ reproductive output, for example.

Known unknowns?

Reflecting on what the project has achieved to date, is it fair to say that we now know where ‘our’ breeding Short-eared Owls mysteriously appear from? Not really, no! Birds that we’ve tracked have wintered in Scotland, southern England, Ireland and Morocco. They seem to be real nomads, exploiting resources that are patchy in both space and time. That’s part of what makes the project exciting though - we really don’t know what’s going to happen next. Follow @BTO_Scotland on Twitter or keep an eye on the project webpage for future updates.

Help fund Short-eared Owl Tracking

As well as the expertise and commitment of John and his team, this project needs financial support. Each tag costs £2,000 and the annual data costs are £1,000. You can help donating to our Short-eared Owl Tracking Appeal. Your support will help this pioneering project to continue.

Acknowledgements

We thank the individuals without whose local knowledge of ‘their’ Short-eared Owls, this work would not have been possible. We are also indebted to the charitable trusts and small group of individuals for their generous donations which have allowed us to make ground-breaking progress on this challenging project. We are especially grateful to Neil Morrison who was key to starting this work in Perthshire, has been in on the tagging of all birds so far, and continues to be key to its progress.

What do you think about modern tracking technology and its use in our research? What gaps in our knowledge do you hope we will one day be able to address? Let us know with a comment below.

Share this page