BirdTrack migration blog (November–December)

Scott’s role includes the day-to-day running of BirdTrack: updating the application, assisting county recorders by checking records and corresponding with observers.

Relates to projects

The continued southerly winds of last week were not ideal for 'classic' autumn migration – spectacles large numbers of birds moving to the UK from their breeding grounds in more northerly latitudes.

However, the southerlies did provide birders with some interest in the form of an influx of Pallid Swifts. It is difficult to get an exact and accurate number of individuals, as these birds were highly mobile and single birds could well have been reported from several locations. Well over 30 sites, mainly along the south and east coasts, saw single or multiple birds during the last week. Many patch birders had their focus fixed firmly on the skies in the hope of spotting one of these aerial masters – although they would then have been faced with the challenge of nailing the birds' identification – Pallid Swift are after all very similar to Swift and they can be very difficult to distinguish.

Both Redwing and Fieldfare continued to arrive, but in much lower numbers than in previous weeks, probably due to the southerly wind direction. Although reports of Waxwing did increase, we are yet to see any major influx - we will have to wait for more favourable weather conditions for that.

Bewick's Swans typically start arriving in early November, but reports have been few and far between so far this year. This could be due to milder weather at more northerly latitudes, reducing the need for the swans to press south, or stormy conditions which have prevented the birds from crossing over the North Sea.

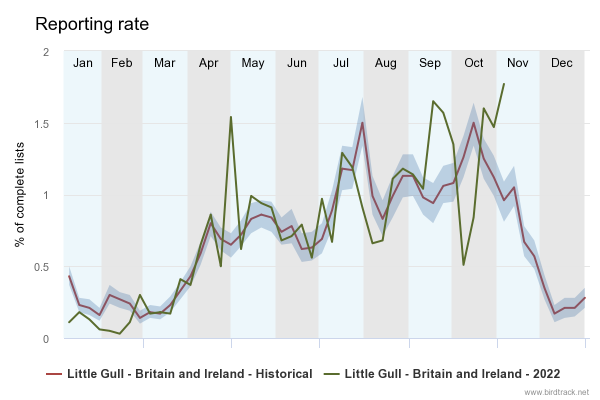

Seawatching was generally good last week, with reports of Cory’s Shearwaters, Grey Phalaropes, Little Gulls, and skuas from several locations, mainly along southwestern coasts. In the case of Little Gull, however, birds were reported all around Britain and Ireland, with over 1,300 passing Flamborough Head on 2 November.

The strong southerlies also brought a scattering of Leach’s Petrels along southwestern coasts. Another seabird species typical for this time of year, it is still one that many birders love to see. Leach's Petrel is a tiny bird, similar in size to a Starling, spending most of its life out at sea; it usually only comes ashore to breed, but sometimes storm-driven birds can turn up on inland waters.

Reports of other more typical winter species steadily increased too, as species such as Lapland Bunting, Snow Bunting, Shorelark, and Short-eared Owl arrived at their traditional wintering areas. The growing numbers of these will partly be driven by the weather conditions both here and across Europe, with colder conditions likely to see numbers rise even further.

Some typical late autumn rarities were also found: a Pied Wheatear in Northumberland, an Isabelline Wheatear in Gwynedd, an Alpine Accentor in Suffolk and another in Norfolk, and a Band-rumped Petrel in Cornwall.

Autumn migration has been a real rollercoaster this year. Very quiet periods have been interspersed with some truly wonderful days as migrating birds poured in across Britain and Ireland. It has certainly also been an autumn of American vagrants, from the first UK record of Least Bittern in Shetland, to the dazzling Blackburnian Warbler in the Isles of Scilly.Scott Mayson, BirdTrack Organiser

Looking ahead

The months of November and December are excellent times of year to look for a range of birds, no matter where you live. They also provide you with time to familiarise yourself with a host of wintering species.

Here are some pointers as to what species to look out for, and where:

Wildfowl

Family groups of Bewick's Swan arriving from Siberia will often mix with Whooper Swans that will have flown from Iceland. These two swan species can sometimes be found together in ‘herds’, favouring arable fields in which they can feed. They will sometimes mix with flocks of grey geese like Pink-footed or Greylag Geese when they first arrive. If you're not yet confident separating these species, why not watch our ID videos for wintering swans and grey geese?

The best sites for watching wintering Barnacle Geese are around the Solway Firth and on Islay, and large numbers of Dark-bellied Brent Geese can be seen around the Norfolk and Lincolnshire coasts. If you're looking for Pale-bellied Brent Geese, head to Lindisfarne, Northumberland or Strangford Lough and Lough Foyle, Northern Ireland.

Groups of dabbling ducks like Wigeon and Teal are always worth a close scan; check for species such as American Wigeon, Green-winged Teal, Blue-Winged Teal, or an over-wintering Garganey. Diving ducks such as Tufted Duck and Pochard often gather in large rafts which can conceal species such as Scaup, Long-tailed Duck, or Smew, or maybe even a Ring-necked Duck or Lesser Scaup.

At this time of year I love listening out for the migrating flocks of Redwing that pass overhead at night, unseen. Looking out of the train window for the first Whooper Swans to arrive on the fields also makes me feel like winter is truly on its way.Tom Stewart, Media Manager

Waders

Any wader flock is worth scanning through in the colder months; they could contain an overwintering individual of species like Little Stint or Curlew Sandpiper.

Arable fields are a great place to watch Lapwing flocks, which often attract Golden Plover during the winter. At inland waterbodies, look out for Green Sandpiper, or maybe even a Turnstone or Knot - both these latter species can be patch birding gold.

Huge numbers of waders winter around the UK's coastline. If you time your visit right – around an hour before high tide – you can watch the encroaching waves flush tens of thousands of birds into the air, forming murmuration-like aerial displays.

A trip to any estuarine site can yield good views of waders, but for the biggest flocks head to the Wash, where over 80,000 Knot come together in the high tide roosts. Good sites in Scotland include the Solway Firth and the Montrose Basin; in Wales, try areas along the Severn estuary; in Northern Ireland, visit Strangford Lough.

Gulls

At this time of year, gulls group together; mixed flocks can often be found on favoured roosting sites like playing fields, refuge tips and reservoirs.

Searching these flocks gives you the opportunity to get familiar with and learn how to distinguish the various plumages of commoner species such as Herring and Lesser black-backed Gulls.

Amongst these, it is worth looking for a wintering Kittiwake, or a Mediterranean, Iceland, or Glaucous Gull. If you're lucky, you may even come across a Ring-billed or Bonaparte’s Gull.

Even if you don't spot anything unusual, it is always keeping a look out for colour-ringed birds. Report these via the European Colour-ring Birding website; as well as providing organisations like BTO with valuable scientific information, it can be fascinating to find out where some of these birds have come from.

I enjoy winter birding as you can never tell when you might stumble across a Woodcock. There could be one watching me right now!Rob Jaques, Supporter Development Officer

Finches and buntings

During the winter, finches often form mixed flocks. These can attract a whole host of unusual species and are well worth taking the time to look through, and to visit regularly if you're able.

Tree Sparrow, Brambling, Reed Bunting, and Corn Bunting will often join flocks of commoner species such as Chaffinch, Yellowhammer, and Linnet, particularly in coastal or arable regions. On the coast, especially in areas like the Northumberland and Norfolk, keep your eyes peeled for wintering Snow Bunting, and don't forget to look out for Twite, too.

You can prepare for the ID challenges which might arise with an unusual species, like Little or Lapland Bunting, with our winter bunting ID video.

Alder trees are a favoured source of food for both Siskin and Redpoll, and both species can sometimes be found feeding on Larch pine cones. It's also worth looking for Common (Mealy) and even Arctic Redpolls among the more numerous Lesser Redpolls.

Tits and warblers

Tit flocks are a firm favourite for birders; they can be a magnet for other passerines, with Chiffchaff, Siberian Chiffchaff, Yellow-browed Warbler, and Firecrest sometimes found in their company.

Whether you see something unusual or not, watching a group of Long-tailed Tits or Goldcrests flit through the branches is delightful, particularly on a frosty morning - listen out for their high-pitched calls as they move through the trees.

These flocks can be found almost anywhere, but scrub around ponds or reedbeds can be particularly productive – even in winter, this habitat provides lots of insects for the birds to feed on.

Most of my memories of winter divers are of hazy grey shapes out to sea - but I will never forget seeing the Red-throated's elegant, upward-sweeping bill in sharp contrast to the powerful dagger of the Great Northern and the sinuous neck of the Black-throated, together, metres away from me in a harbour on Islay.Miriam Lord, Website Editor

Seabirds

This is a particularly good time to look for species that spend the winter in our coastal waters.

Divers and Grebes can be found all around our coasts and are often found side by side. Red-throated Divers are by far the commonest species to see; their habit of pointing the bill slightly upward is a good identification feature. Smaller numbers of Black-throated and Great Northern Divers are sometimes mixed among them, with harbours and larger inland water bodies being good locations to check. Learn how to tell these three species apart during the winter months in our winter divers ID video.

Great Crested Grebes can look a little out of place when seen sitting on the sea, but small groups often feed a few hundred metres offshore. These groups can conceal a Red-necked, Slavonian, or Black-necked Grebe. However, it’s often best to look for these scarcer grebes on reservoirs and larger lakes. You can brush up on your winter grebe ID with our video covering all four of these species.

The males are dressed in strict formal wear, black and white with the faint flush of a winter sunrise on their breast, and stylishly offset with a subtle sage nape. Females flock in their cryptic speckled cinnamon. A raft of Eider in winter is an unsung spectacle.Katherine Booth Jones, Senior Research Ecologist

Seaducks form large mixed rafts on the water during the winter months, with hundreds of birds such as Scoter and Long-tailed Duck flocking together.

Rafts like these are always worth scrutinising in case there is something more unusual amongst the commoner species. Look out for Velvet Scoter, Long-tailed Duck and Scaup, or maybe something rarer like King Eider or Surf Scoter. It can be surprisingly straightforward to identify the different scoter species, even when they are far out at sea; learn how in our scoter ID video.

Other species to look out for

November is also the prime time to keep a lookout for rare and scarce species - which species these might be is largely dependent on the prevailing winds.

After strong northerlies, keep your eyes peeled for Little Auk around the coast, and even on inland water bodies after a particularly strong storm.

Easterlies are more likely to bring birds such as Hume's Warbler or Desert Wheater to our shores.

The 'wink-wink' calls of a skein of Pink-footed Geese overhead really lift my spirits - I think I'd find that the dark and cold of winter affected my mental health more if it wasn't for birding.Sorrel Lyall, Ripple Project Officer and Interim NI Engagement Coordinator

Send us your records with BirdTrack

In the midst of an Avian Influenza outbreak, your birdwatching records are more important than ever.

Submitting your sightings to BirdTrack is quick and easy, and gives us vital information about our wintering birds.

Find out more

Share this page